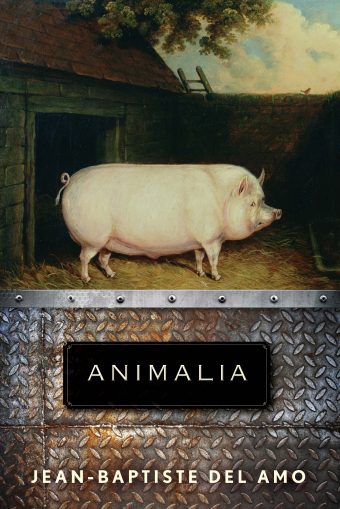

Monday, February 24, 2020 - No one wants to face the reality of factory farming: billions of  animals, hidden away in warehouses, who live and die in constant pain, confinement and abuse. The more you look at it, the less sense it makes, and the more incomprehensible it is that we have allowed it to happen. “Animalia,” the newly translated novel by French author Jean-Baptiste Del Amo, doesn’t make the madness of industrial animal agriculture comprehensible, exactly, but it does render it more clearly.

animals, hidden away in warehouses, who live and die in constant pain, confinement and abuse. The more you look at it, the less sense it makes, and the more incomprehensible it is that we have allowed it to happen. “Animalia,” the newly translated novel by French author Jean-Baptiste Del Amo, doesn’t make the madness of industrial animal agriculture comprehensible, exactly, but it does render it more clearly.

“Animalia” follows five generations of a family in the southern French village of Puy-Larroque, from the turn of the 20th century through World War I and into the 1980s. Their dirt-poor, miserable patch of land, with a few animals raised in confinement, develops into a vast industrial pig farm, or piggery, as translator Frank Wynne faithfully renders from the French porcherie.

To American readers who associate the French countryside with scenes of bucolic bliss, France as the site of brutal, industrialized farming practices might come as a surprise. At a September 2019 talk, Mr. Del Amo explained that details from “Animalia’s” piggery were taken directly from his visits to French factory farms. What he saw there was so terrible that he knew he wanted to write about it — that fiction would allow him to be more honest about animal agriculture than filming it.

Mr. Del Amo’s immersive prose imagines what it is like to try to handle these farms. When a mysterious illness breaks out among the pigs, he writes, “thick, blood-streaked pus flows off their vulvas and collects in large pinkish pools that mingle with the [excrement] on the floor of the pens. Joël tries to help them stand. He pushes at their rumps, desperately beats them with a stick. They try to stand in order to get away from him, but collapse under their own weight. They shriek, and he begins to shriek with them.”

It would have been easy to draw a bright line separating the horror of the present and farming practices of the past. But the novel suggests that the idea of small, humane family farms is an invention of modern nostalgia. In the early 20th century, while the matriarch Eléonore is still a girl, the family’s pigs are bred on a smaller scale, but they are no less abused; it makes it seem quaint to think that animals raised for food could ever be treated with compassion. By linking the horrors of past and present, Del Amo tells a story of how modernity has industrialized and optimized human cruelty. The patriarch Henri always mutters about improving the farm’s “efficiency”; the piggery “constantly produced more, proportionally increasing their workload and their violence.”

The earliest roots of industrial agriculture in “Animalia” come when, during World War I, all of the local families’ animals are requisitioned, hauled away to be quickly slaughtered for soldiers at war. “The pace of the slaughter is such that none of the men has seen its like before,” Mr. Del Amo writes. “They come to hate these animals, who show so little goodwill in their dying ....They hack at their hindquarters with blades to urge them on .... A boy of twenty breaks down and weeps. He is cradling the remains of a newborn kid goat he cut from its mother, which laid its head against his neck and suckled his earlobe as he carried it to the slaughtering tents.”

The animals march to their deaths in these unfamiliar, frightening surroundings, mirroring Jean-Baptiste Del Amo’s depiction of the marching soldiers themselves, sent to die for a cause no one understands. “Animalia” is full of parallels like these, but it rarely draws them directly. It invites readers to connect the tangled web of violence, against people and animals — and face the brutality in which all of us are complicit.

Learn More at the Original Article Here